Rio de Janeiro – also known as A Cidade Maravilhosa, the Marvelous City – is one of the most beautiful cities on the planet. Its many attractions include its world-famous beaches, Carnival, Christ the Redeemer statue, and Sugarloaf Mountain, as well as many more besides. Put together, these form a picture-perfect postcard dominated by the 4 Ss of Rio life: sun, sand, samba, and soccer.

However, this is only one side of the story. For many of the city’s residents, this paradisical image couldn’t be further from the challenges of their daily realities.

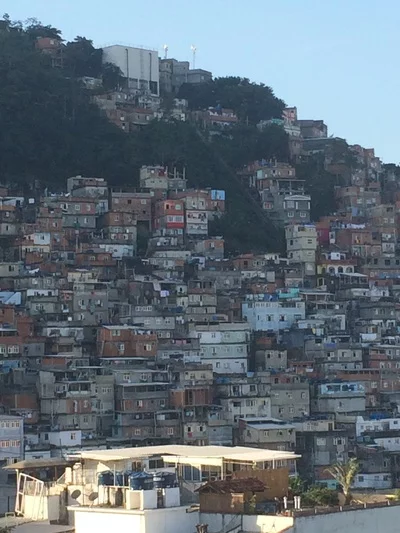

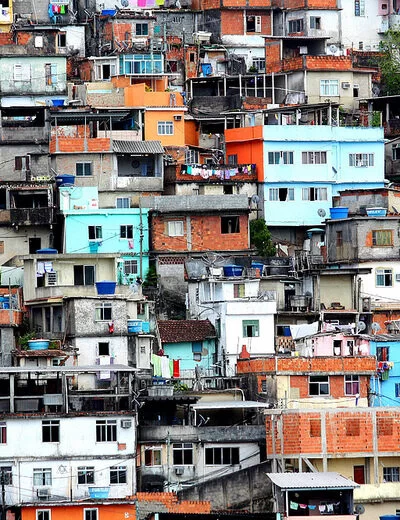

Although precise figures are difficult to determine, some 2 million people, about 20% of Rio’s population, live in 1000 neighbourhoods known as favelas. These are “settlements characterized by informal buildings, low-quality housing, limited access to public services, high population density, and insecure property rights.”

EduMais works in four such favelas, Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo, known collectively as PPG… EduMais also operates in Tabajaras. All four favelas are located in Copacabana, they form a dramatic contrast to the wealth of Rio’s South Zone.

According to the 2010 census, PPG’s combined population is just over 10,000. However, due to the difficulties for census takers in favelas, the real population is likely to be double that.

Over 4,000 children and teenagers make up this probable population of 20,000 people. Of these:

50% live in poverty

14% are at-risk of dropping out of education

6.2% are out-of-school children

Although the UPP pacified Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo in 2009, these young people still face daily challenges. These include drug trafficking violence, poverty, sexual abuse, food insecurity, and home instability.

We believe they have the same right to a good education and peaceful life as their wealthier neighbours. EduMais’s mission is thus to equip them with the tools and skills to build a brighter future for themselves.